by Sarah Ripper; UPLIFT

Understanding the Connection

You have more in common with trees than you think. It’s not such a weird idea when the emerging field of plant neurobiology is seeing increasing collaborations with other fields into the nature of plant intelligence. These studies are prompting scientists and spiritual communities, such as Damanhur, to reconsider the scope of communication and adaptation found in nature.

From a spiritual perspective, plants can be viewed as the ultimate alliance for human beings as all life forms part of a spiritual ecosystem where matter and form co-exist. Within this co-existence, the environment is an integral part of leading a holistic and balanced life. Science is beginning to echo what indigenous peoples, tree-huggers, shamans and spiritual teachers have been saying for a very long time. We do have far more in common with our leafy friends than we once thought.

Is being more sensitive to plant’s feelings the key to future adaptation? Well, plants have scientifically documented senses just like humans and animals. Thanks to plant neurobiology’s use of human analogies we can begin to understand how plants experience senses. According to Professor Stefano Mancuso, who leads the International Laboratory for Plant Neurobiology at the University of Florence, plants are a lot more sensitive than animals. He discovered that the very root apex of a plant has the capacity to detect 20 different physical and chemical parameters including gravity, light, magnetic field pathogens and more.

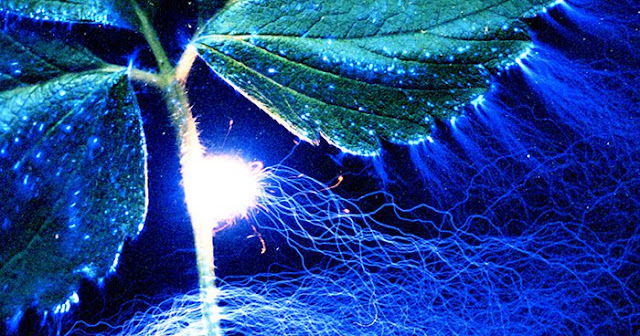

Plants have genes similar to those of an animal nervous system, specific proteins that have been shown to have definite roles in neural function and whilst they are not exactly the same as those found in animals, they are believed to behave in very similar ways. Through recognizing the sensory capacity of the ‘wood wide web’, a term coined by Professor Suzanne Simard, to describe the interconnectedness of trees, perhaps we’ll look at their sensory expressions a little differently.

The Importance of Our Plant Life

We know we need plants to live. With a rapidly altering natural environment, human population increasing, and changes in weather patterns, particularly precipitation, it’s important for us to know how plants sense, adapt and respond to their environment if we are interested in protecting biodiversity, eating plant-based ingredients and, you know, breathing clean air. Professor Daniel Chamovitz of What a Plant Knows regards the complex biology of plants as being completely underappreciated and underestimated, and claims that if we do not embrace and learn from the amazing complexity of plant life, we may find a host of big problems awaiting us in 50 to 100 years time.

According to Damanhur’s founder, Falco Tarassaco, during the past few decades more old growth forests have been destroyed than throughout humankind’s presence since the Palaeolithic period. He claimed that within 50 years, 50% of all our planets trees have been felled. These perspectives or statistics may differ but they make a resounding point – nature is inseparable from human life, it needs to be respected and protected.

Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better. – Albert Einstein

If we take a closer look, here are a few things we humans have in common with trees.

We Experience Time

We both experience the passing of time. From a Damanhurian perspective, plants have a longer and slower experience of time and life than humans, and an ability to store collective memory. Trees synthesize subtle and gross forms of energy to feed themselves – light, water, and nutrients from the soil; the quantity and quality playing a key role in their overall health and vitality. The electrical signals in a tree’s tissues travel approximately one to two seconds per inch meaning their reaction to events takes place within minutes, hours or days. Because these signals can take several minutes to travel from the crown of the tree to the roots, trees simultaneously transfer information through chemical signals sent out from their leaves.

We Need Food and Rest

A recent Hungarian-Finnish-Austria study showed us that trees also need their rest with the circadian rhythm being measured by the drooping of leaves overnight, seen as a form of tree sleep. Using laser scanners, so as not to disturb the exposure the trees had to light, the branches of 5-metre birch trees progressively drooped by 8 to 10 centimeters, with their lowest position right before sunrise, and then returning to full form a few hours after sunrise. It has not yet been determined whether the rays of the sun, the trees’ own inner rhythm or a combination of the two induce this tree sleep.

We Digest

Humans, animals, and plants share some digestive similarities, microbiological similarities – all of them sustain microcolonies that in turn sustain them. A plant uses their external ‘guts’ (roots) which somewhat simplifies the study, in comparison to the internal human and animal guts. Yet scientists have found the microbial ecologiesthat reside in all these forms of life and considerably impact the development, health, and wellbeing of their respective hosts.

These microbial helpers share similar job descriptions as they play a key role in gene expression, metabolic processes, and protection against pathogens, and even share evolutionary trends. Just as food quality and choices affect the human digestive system and well-being, so too does the soil health affect the health of plant life.

If we could see the miracle of a single flower clearly, our whole life would change. – Gautama Buddha

We Pass on Information

Both humans and plant life have an intergenerational exchange of knowledge.

Damanhurian researchers claim that if we detach from the green brain (the collective plant knowledge of the planet), we detach from a connection with planetary memory. This connection serves humankind in terms of biodiversity and spiritual knowledge, as well as limiting the knowledge we can access of the human and planetary experience, which goes well beyond what has been documented by historians in various world cultures.

Scientists are discovering not only that neurotransmitter molecules facilitate cell-to-cell communication, and that the exchanging of carbon from a dying tree to its neighbors has been measured, but also that the study of plant intelligence requires an integrated approach to plant signaling, adaptive behavior and it’s potential impacts for the future. It also reflects back to us this cyclical and intrinsic collective coexistence. We are not as dissimilar to plant or animal life as we think we are. We grow, we shed, and we adjust to the seasonal rhythm of our climate. Just as modern mystic Sadhguru said:

You may attach much of your birth, life, and death, but for Mother Earth, it is just a recycling process.

The knowledge that is exchanged between trees can be viewed akin to the intergenerational passing on of mythology, language, or family stories, tribal information or spiritual teachings.

Nature does nothing without purpose or uselessly. – Artistotle

We Have Social Networks

The interconnectedness of trees is taken further by German forester and author, Peter Wohlleben, in his best-selling book the Hidden Life of Trees, which draws on revolutionary scientific discoveries as well as many anthropomorphic examples to describe the social network and family structure of trees. Wohllenben explains how tree parents ‘suckle their children’ and suggests that mother trees even have favorites! These family chats enable trees to share nutrients with those who are sick or struggling, warn of forthcoming dangers or adjust to weather conditions such as droughts by altering their water consumption strategies to conserve energy.

Through understanding forests as a network, Wohlleben believes foresters and plantation workers are able to foster healthier trees producing more timber and living possibly double the lifespan if their social network is not interrupted by thinning methods which leaves a tree ‘single’. For trees in protected natural habitats, the social relationships amongst and between species have another level of depth.

This world is indeed a living being endowed with a Soul and intelligence… a single visible living entity containing all other living entities, which by their nature are all related. – Plato

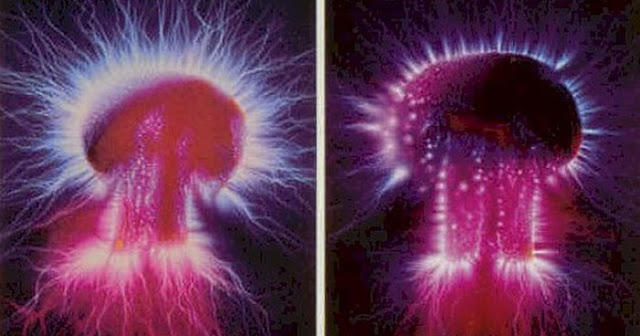

The green brain of knowledge and social network mirrors our human family’s, or community’s, need to belong and contribute to the whole. Damanhurian teachings ask people to consider that what we see of a tree is actually the plant’s skeleton; the rest of it is its energy system. The trees’ aura contains parts of its form that cannot be seen by the untrained eye but can be felt with practice when sensitizing the hands to feel the subtle energy and walking around the tree to feel its aura.

These processes are subtle, and their capacity to be measured by our physical senses or diagnostic tools is limited. However, the Music of the Plants device is a bridge to this type of understanding, whereby the plants’ vibration is converted into musical tones and communicated to humans. The plants have to ‘learn’ how to use this device and, through years of experimentation, Damanhurians have observed that plants tend to do a scale once they are connected to the machine, just before they play. They think this is for the plant to understand the tonal possibilities. It’s also been observed that potted plants have a higher pitch than plants in the ground. I saw a potted plant connected to the device ‘jam’ with an old oak tree it was placed beside. The difference in tone and ‘call and response’ was a tangible and fascinating example of plant communication.

We Have the Potential for Continual Evolution and Innovation

The observation of plant signaling, communication, adaptive behavior and purposeful interrelating with other trees fuels plant science, and its potential applications and implications for sustainability and research. As human consciousness expands, perhaps so too does the scope science is capable of measuring and considering. Biomimicry has already seen an exciting shift in seeking solutions for problems through nature’s answers – from mosquito inspired ‘nicer needles’, to what termites can reveal about construction. A new field of bio-robotics is also developing which could also be used for lots of purposes, including space applications or environmental monitoring.

Emerging planetoid robots are using the natural function of plant intelligence to gather data for scientific research. This would have a trunk, branches, and leaves, just as a real plant, along with artificial roots, which would be constructed from 3D printers. These robots could be tailor made for specific needs to further our understanding of the environment both on this planet and beyond. With what we are beginning to learn about plants and their thinking, sleeping, and family relationships and their applications, a new chapter is emerging. As we expand what there is to know, we expand our possibilities.