Dave Mosher 27 May 2018

Foto: Copyright of Linden Gledhill

After a long work day, most of us happily collapse into a couch and binge-watch our favorite show.

But Linden Gledhill, a Philadelphia-based pharmaceutical biochemist, retreats to his basement lab. There, he builds custom gear so that he can record the beautiful, complex, and sometimes very weird intersection of science, art, and nature.

For example, Gledhill hacked an old hard drive into a camera shutter 10 times faster than anything in a store. He’s also rigged up a machine to create snowflakes on demand and patented a super-resolution photography rig.

Gledhill uploads his experimental photos and video to Flickr, and art directors and producers take notice – not only because he’s creative, but also because he’s good. He’s earned commissions for TV commercials and music videos, and most recently, high-tech prints of his photos were donned by fashion models. AdvertentieMeer weten?

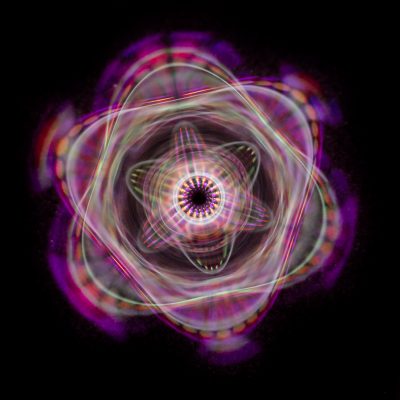

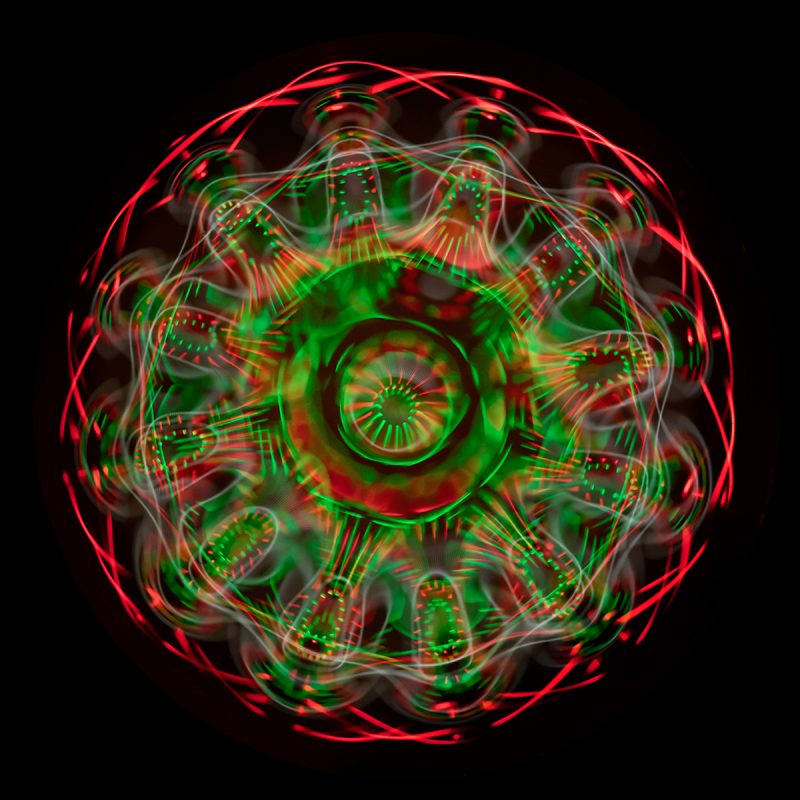

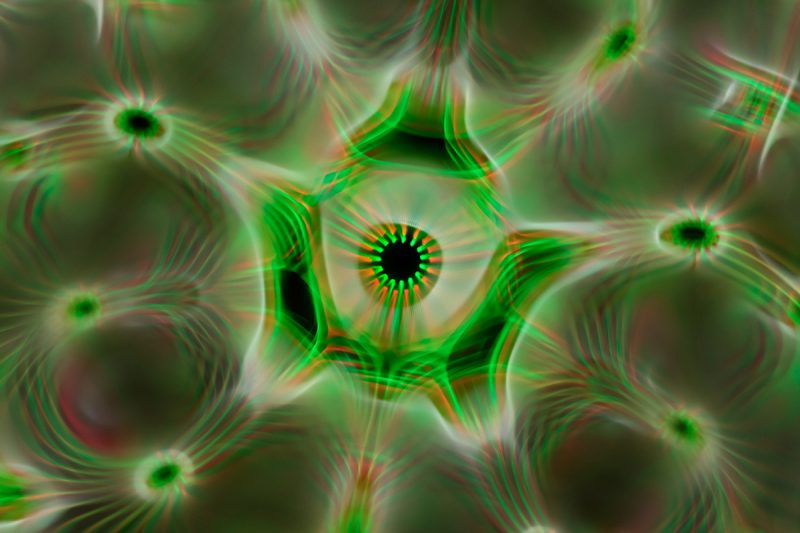

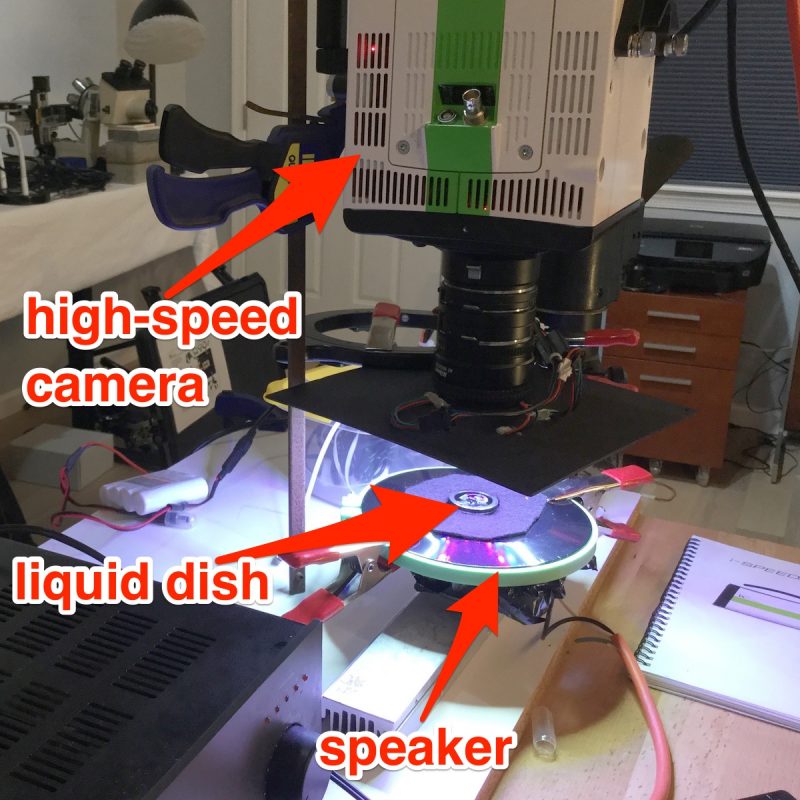

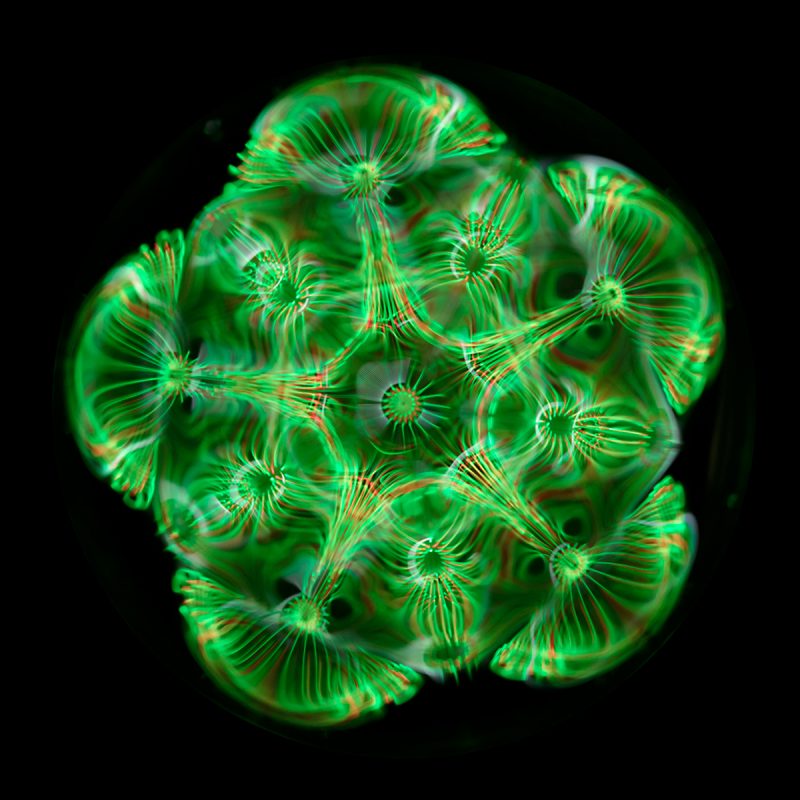

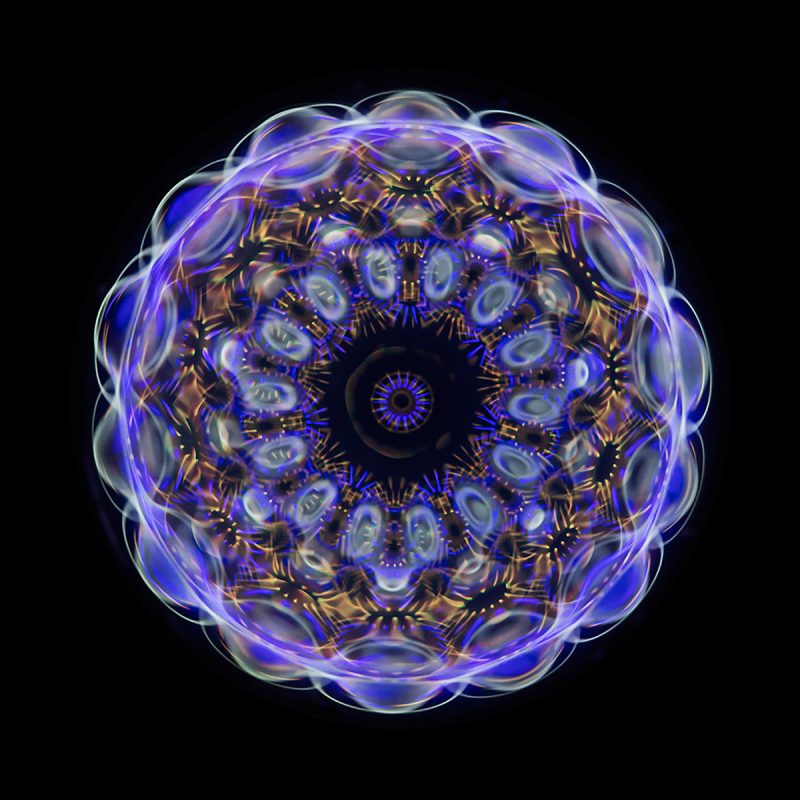

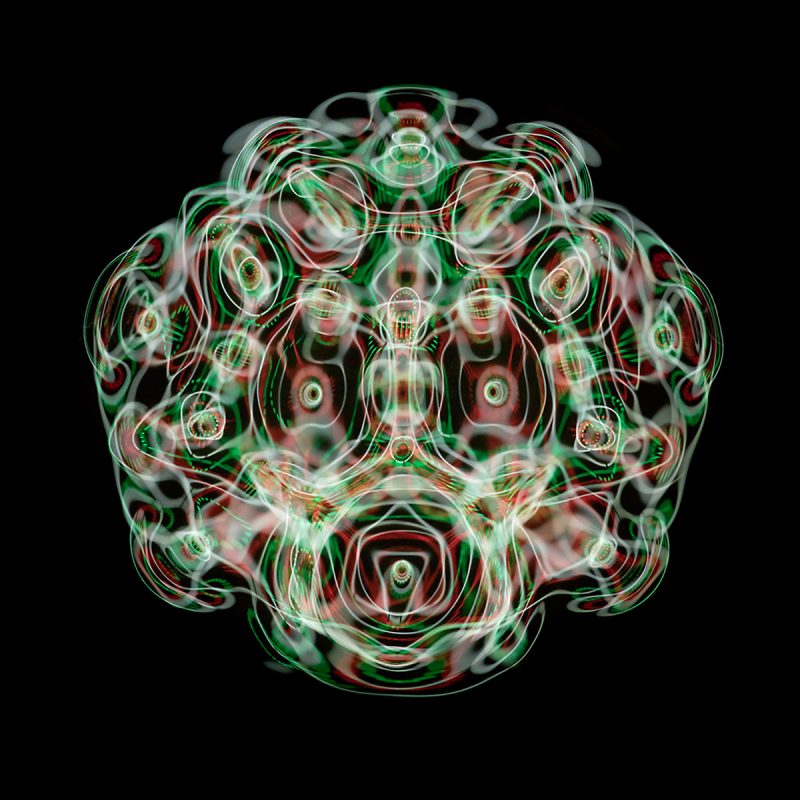

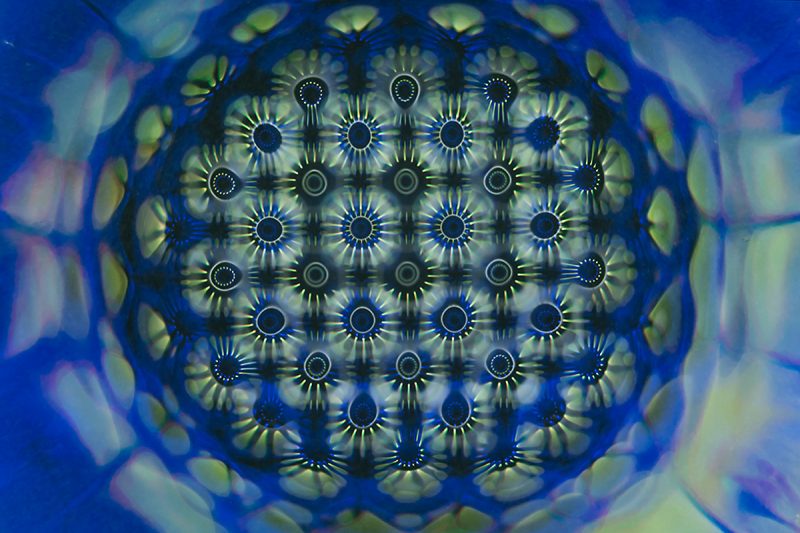

For the past couple of years, Gledhill has been playing with a tiny dish of liquid that sits on a speaker. Called a cymascope, it’s designed to create and tune repeating patterns of waves, like those formed in wine by rubbing the rim of a crystal glass to make it vibrate or “sing.” These cyclical ripples, also called cymatics, travel far faster than human eyes can see, so he uses ultra-high-frame-rate cameras slow them down and record their secrets.

“It allows you to see the individual vibration states throughout the cycle. That’s pretty cool. Typically you don’t get to see that,” Gledhill told Business Insider. “Typically what you see is a fixed pattern or a changing pattern based on the frequencies you play through the liquid.”

Here’s a look at some of Gledhill’s newest experimental and hallucinatory imagery.

Gledhill started experimenting with standard macro-photography camera gear. He took images of a roughly one-inch-wide, quarter-inch-deep dish of water vibrated by a speaker.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

The camera peers down on the dish through a an LED light ring, which evenly illuminates the liquid in the dish. (In this case, malt whiskey.) The light ring is visible in a reflection at the center of this image.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

Here’s a photo of Gledhill’s cymascope rig at his home.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

By changing the colors of the LEDs and the frequency of sound, he can produce a diverse array of patterns as sound waves bounce off the sides of the dish, repeatedly cycling back and forth.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

Where waves meet and add up, they create nodes. When ripples cancel out, troughs appear.

“They’re highly complex, and the phenomenon creates huge ranges of patterns,” Gledhill said. Higher frequencies result in more intricate ripples in the water that distort and reflect the LED light in wild ways.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

Frequencies toward the lower range of human hearing, at around 20 Hertz (cycles per second), produce larger patterns. Gledhill thinks this one resembles an alien head.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

And he thinks this pattern — recorded in a mix of 90% rubbing alcohol and 10% water — looks somewhat like sheep.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

This one looks a bit like a wormhole in space.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

At certain frequencies, the waves resonate perfectly to create Faraday or standing waves. Basically, the waves line up so well, the liquid takes on a pattern that doesn’t appear to move.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

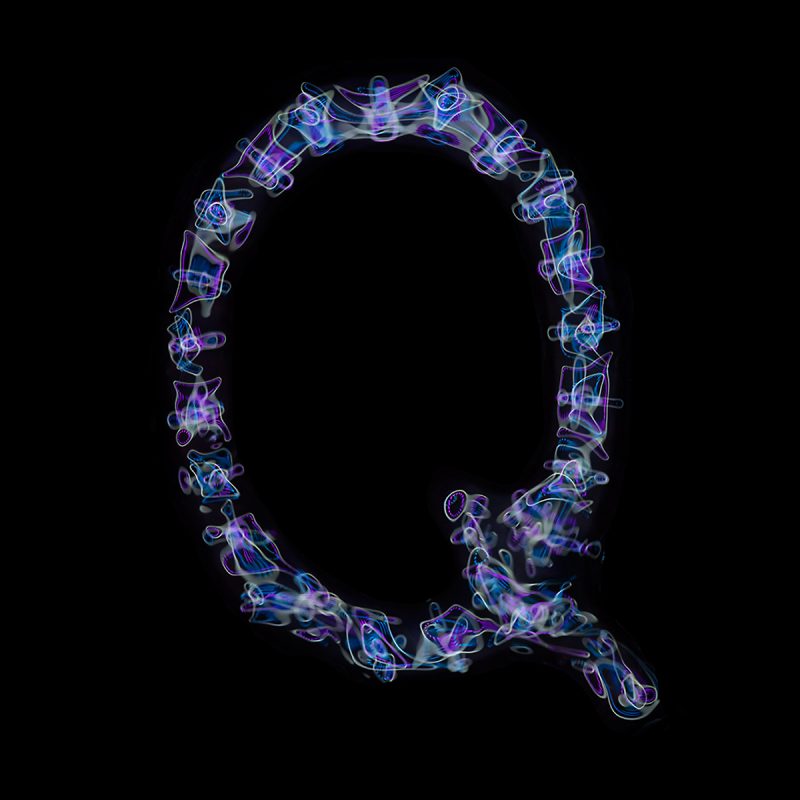

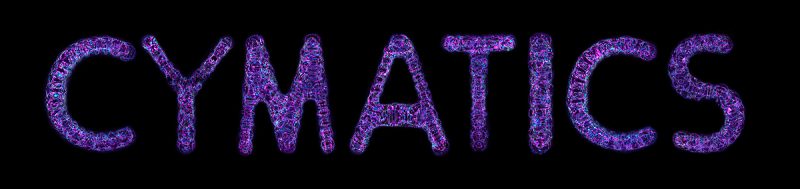

Gledhill eventually tried different containers for liquids, including plastic refrigerator-magnet letters with hollow backs.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

The word “cymatics” is cleverly spelled out here in several images of refrigerator magnets. The term is derived from the Greek word for wave. It describes any visible repeating wave pattern through a medium — water in this case.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

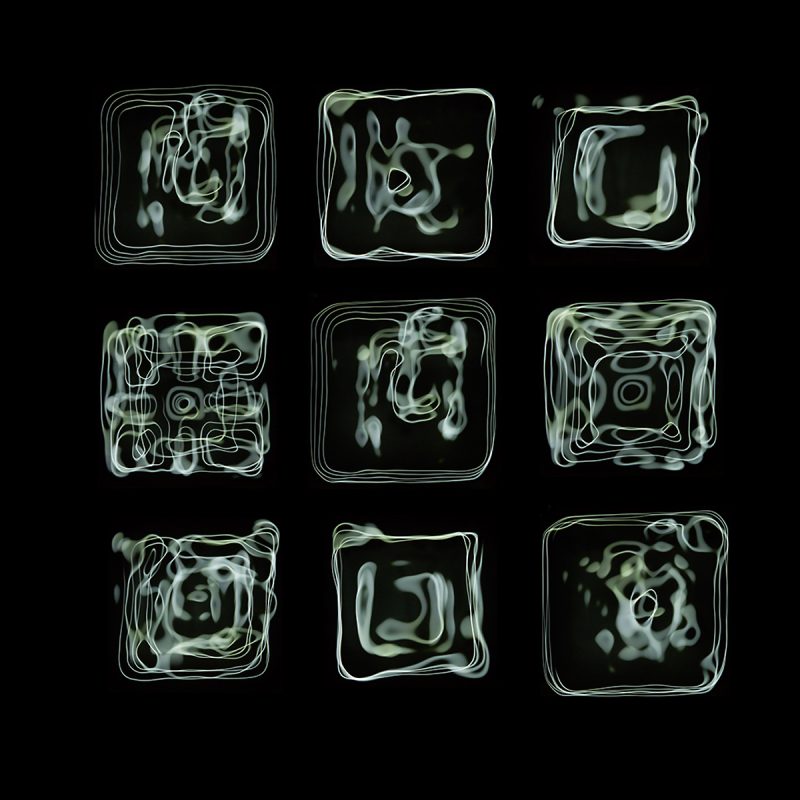

Gledhill also used square dishes to create cymatic images. This one became a music album cover.

Foto: source Copyright of Linden Gledhill

Source: Discogs